Gamecock Fanatics

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Countdown to Kickoff II: The Final 24 Days

- Thread starter Swayin

- Start date

USS Langley (CV-1)

_underway_in_June_1927_(cropped).jpg/1920px-USS_Langley_(CV-1)_underway_in_June_1927_(cropped).jpg)

.jpg)

The devastating crew losses of the Langley, Pecos, and Edsall in the early part of the war are a rarely talked about footnote of WW2 that demonstrate the absolutely ruthless nature of the old Japanese empire back then.

_under_fire_and_sinking_on_1_March_1942_(80-G-178997).jpg/1920px-USS_Edsall_(DD-219)_under_fire_and_sinking_on_1_March_1942_(80-G-178997).jpg)

_underway_in_June_1927_(cropped).jpg/1920px-USS_Langley_(CV-1)_underway_in_June_1927_(cropped).jpg)

Photo of the first U.S. aircraft carrier USS Langley (CV-1) after conversion into a seaplane tender, designated USS Langley (AV-3), in 1937. (below)USS Langley (CV-1/AV-3) was the United States Navy's first aircraft carrier, converted in 1920 from the collier USS Jupiter (Navy Fleet Collier No. 3), and also the US Navy's first turbo-electric-powered ship. Conversion of another collier was planned but canceled when the Washington Naval Treaty required the cancellation of the partially built Lexington-class battlecruisers Lexington and Saratoga, freeing up their hulls for conversion to the aircraft carriers Lexington and Saratoga. Langley was named after Samuel Pierpont Langley, an American aviation pioneer.

Following another conversion to a seaplane tender, Langley fought in World War II. On 27 February 1942, while ferrying a cargo of USAAF P-40s to Java, she was attacked by nine twin-engine Japanese bombers of the Japanese 21st and 23rd Naval Air Flotillas and so badly damaged that she had to be scuttled by her escorts.

.jpg)

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/USS_Langley_(CV-1)World War II

On the entry of the US into World War II, Langley was anchored off Cavite, Philippines. On 8 December, following the invasion of the Philippines by Japan, she departed Cavite for Balikpapan in the Dutch East Indies. As the Japanese advance continued, Langley proceeded to Australia, arriving in Darwin on 1 January 1942. She then became part of the American-British-Dutch-Australian Command (ABDACOM) naval forces. Until 11 January, Langley assisted the Royal Australian Air Force in running anti-submarine patrols out of Darwin.

Langley went to Fremantle to pick up a cargo of 32 P-40 fighters of the Far East Air Force's 13th Pursuit Squadron (Provisional), along with U.S. Army Air Force (USAAF) pilots and ground crews. At Fremantle, Langley and the cargo ship Sea Witch (loaded with an additional 27 unassembled and crated P-40s), joined Convoy MS.5 which had just arrived from Melbourne bound for Colombo, Ceylon with troops and supplies eventually destined for India and Burma.

The convoy was composed of the United States Army Transport Willard A. Holbrook and the Australian troop transports Duntroon and Katoomba, escorted by the light cruiser USS Phoenix. MS.5 departed Fremantle on 22 February. En route to Colombo, Langley and Sea Witch were directed by ABDACOM to leave the convoy and instead proceed individually to deliver the planes to Tjilatjap, Java.

In the early hours of 27 February, Langley rendezvoused with the destroyers USS Whipple and USS Edsall, which had been sent from Tjilatjap to escort her. Later that morning, a Japanese reconnaissance aircraft located the formation. At 11:40, about 75 mi (121 km) south of Tjilatjap, the seaplane tender, along with Edsall and Whipple were attacked by sixteen (16) Mitsubishi G4M "Betty" bombers of the Imperial Japanese Navy Air Service's Takao Kōkūtai, led by Lieutenant Jiro Adachi, flying out of Denpasar airfield on Bali, and escorted by fifteen (15) A6M Reisen fighters.

Rather than dropping all their bombs at once, the Japanese bombers attacked releasing partial salvos. Since they were level bombing from medium altitude, Langley was able to alter helm when the bombs were released and evade the first and second bombing passes, but the bombers changed their tactics on the third pass and bracketed all the directions Langley could turn. As a result, Langley took five hits from a mix of 250 and 60 kilograms (550 and 130 pounds) bombs as well as three near misses, with 16 crewmen killed. The topside burst into flames, steering was impaired, and the ship developed a 10° list to port. Langley went dead in the water as her engine room flooded. At 13:32, the order to abandon ship was passed.

After taking off the surviving crew and passengers (Whipple rescued 308 men and Edsall 177 survivors) at 13:58, the escorting destroyers stood off and began firing nine 4-inch (100 mm) shells and two torpedoes into Langley's hull at 14:29 to prevent her from falling into enemy hands, scuttling her at approximately 8°51'04.2"S 109°02'02.6"E.

After being transferred to the oiler USS Pecos, many of Langley's crew were lost when Pecos was sunk en route to Australia by Japanese carrier aircraft. Thirty-one of the thirty-three pilots assigned to the USAAF 13th Pursuit Squadron (Provisional) being transported by Langley remained on Edsall to be brought to Tjilatjap, but were lost when she was sunk on the same day by Japanese warships while responding to the distress calls of Pecos.

The devastating crew losses of the Langley, Pecos, and Edsall in the early part of the war are a rarely talked about footnote of WW2 that demonstrate the absolutely ruthless nature of the old Japanese empire back then.

USS Edsall sinking. (below)At 1550 hours (USN/local time) a single "light cruiser" was spotted about 16 miles (26 km) behind the Japanese task force, approximately 250 miles (400 km) SSE of Christmas Island; this was in fact Edsall. The destroyer was perhaps no more than 38–54 kilometres (24–34 mi) from the last reported position of Pecos and likely attempting to get to her stricken comrades. At about 1603 hours she was seen from the Japanese heavy cruiser Chikuma and within five minutes the cruiser opened fire with her 8-inch (203 mm) guns.

Fifteen minutes later the battleships of Vice Admiral Gunichi Mikawa's Sentai 3/1 (Hiei and Kirishima) opened fire with their main battery of 14-inch (356 mm) guns at extreme range (27,000 metres (30,000 yd)). All shots missed as the destroyer conducted evasive maneuvers that ranged from flank speed, about 26 knots (48 km/h; 30 mph) to full stop, with radical turns and intermittent smoke-screens.

Edsall also disrupted the Japanese with counter-attacks, firing her torpedoes and with 4-inch gunfire. Edsall signaled that she had been surprised by two enemy battleships; this was copied by the Dutch merchant ship Siantar more than 160 kilometres (99 mi) away.

The Japanese surface vessels (2 cruisers, 2 battleships) fired 1,335 shells at Edsall that afternoon with no more than one or two hits, which failed to stop the destroyer. Vice Admiral Nagumo ordered airstrikes: 26 Type 99 divebombers (Aichi D3A) (kanbaku) in three groups (chutai) took off from the carriers Kaga, Hiryū, and Sōryū. The dive bombers were led by Lieutenants Ogawa, Kobayashi, and Koite respectively. Their 250 kg (550 lb) bombs immobilized Edsall.

At 17:22 the Japanese ships resumed firing on the destroyer. A Japanese cameraman, probably on the cruiser Tone, filmed about 90 seconds of her destruction. (A single frame from this film was culled for use as a propaganda photo later, misidentified as "the British destroyer HMS Pope".) Finally, at 17:31 hrs (19:01 IJN/Tokyo time) Edsall rolled onto her side, "showing her red bottom" according to an officer aboard the Japanese battleship Hiei, and sank amid clouds of steam and smoke.

_under_fire_and_sinking_on_1_March_1942_(80-G-178997).jpg/1920px-USS_Edsall_(DD-219)_under_fire_and_sinking_on_1_March_1942_(80-G-178997).jpg)

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/USS_Edsall_(DD-219)The fate of Edsall's survivors

Japanese Imperial Navy officers aboard the cruiser Chikuma several years later reported that a number of men may have survived the sinking of Edsall as they were found in the water on life rafts, cutters or clinging to debris. However, due to a submarine alert, the Japanese only stopped long enough to rescue a handful (the Japanese word is jakkan) before they received orders to retire, leaving the others to perish in the Indian Ocean.

Onboard Chikuma the survivors were interrogated by their captors, giving the name of their ship as "the old destroyer E-do-soo-ru". After a few days, the details of these interrogations were shared with the other ships of Nagumo's Kido Butai during their return journey. There is some suggestion that the cruiser Tone may have picked up a survivor or two as well, but there is no confirming evidence of this. The Americans were held on Chikuma for the next ten days before returning to the Japanese force's advance base on 11 March 1942.

Mass grave

On 21 September 1946 several mass graves were opened in a remote locale in the East Indies, over 1,000 miles (1,600 km) from where Edsall had disappeared. Two graves contained 34 decapitated bodies among which were the remains of six Edsall crewmen and what are thought to be five USAAF personnel from Langley, along with Javanese, Chinese, and Dutch merchant sailors from the Dutch merchant-ship Modjokerto, sunk the same day as and in the same general area as Edsall. The American bodies were reinterred in U.S. cemeteries between December 1949 and March 1950.

War crimes trials conducted in 1946–1948 concerning other murders that occurred in or near Kendari by IJN personnel contain fragmentary information about the killings of Edsall survivors but were not recognized as such by Allied investigators, and were not pursued.

Last edited by a moderator:

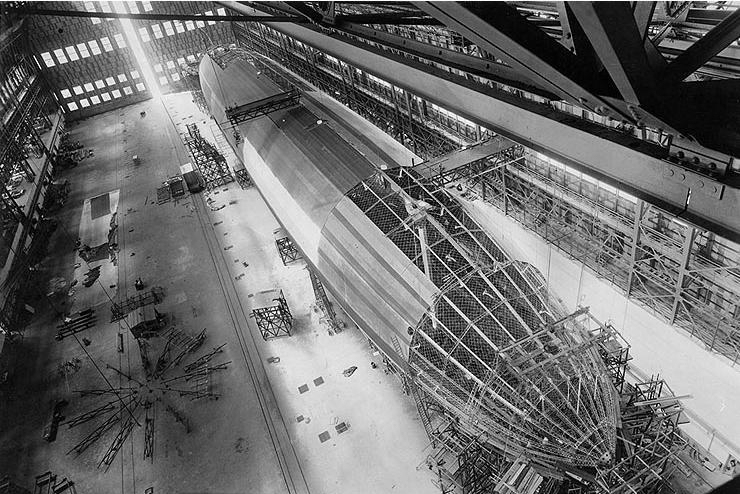

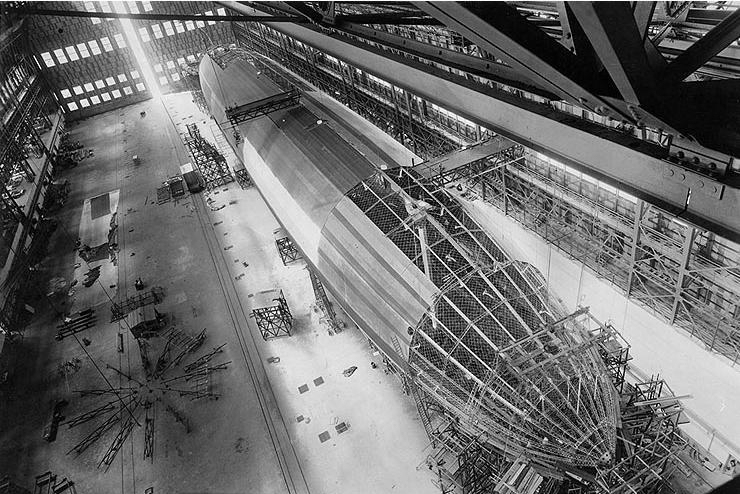

The airship USS Shenandoah (ZR-1)

USS Shenandoah (ZR-1) Under construction inside the airship hangar at Naval Air Station Lakehurst, New Jersey, 1923. This view looks aft, with her nose structure in the lower right. Note the jig on the hangar floor, lower left, used for the assembly of the airship's frames. (Collection of Admiral Thomas C. Kinkaid, USN, 1973)

From 1938 to 1941, Kinkaid was a naval attaché in Italy and Yugoslavia. In the months prior to U.S. entry into World War II, he commanded a destroyer squadron. Promoted to rear admiral in 1941, he assumed command of a U.S. Pacific Fleet cruiser division. His cruisers defended the aircraft carrier USS Lexington during the Battle of the Coral Sea and USS Hornet during the Battle of Midway.

After that battle, he took command of Task Force 16, a task force built around the carrier USS Enterprise, which he led during the long and difficult Solomon Islands campaign, participating in the Battles of the Eastern Solomons and the Santa Cruz Islands. Kinkaid was placed in charge of the North Pacific Force in January 1943 and commanded the operations that regained control of the Aleutian Islands. He was promoted to vice admiral in June 1943.

In November 1943, Kinkaid became Commander Allied Naval Forces South West Pacific Area, and Commander of the Seventh Fleet, directing U.S. and Royal Australian Navy forces supporting the New Guinea campaign. During the Battle of the Surigao Strait, he commanded the Allied ships in the last naval battle between battleships in history.

Some of the older naval aviation officers and enlisted men who fought in WW2 were undoubtedly involved in airship operations during the 1920s and 1930s.

Shenandoah under construction at Lakehurst in 1923. (below)USS Shenandoah was the first of four United States Navy rigid airships. It was constructed during 1922–1923 at Lakehurst Naval Air Station, and first flew in September 1923. It developed the U.S. Navy's experience with rigid airships and made the first crossing of North America by airship. On the 57th flight, Shenandoah was destroyed in a squall line over Ohio in September 1925.

USS Shenandoah (ZR-1) Under construction inside the airship hangar at Naval Air Station Lakehurst, New Jersey, 1923. This view looks aft, with her nose structure in the lower right. Note the jig on the hangar floor, lower left, used for the assembly of the airship's frames. (Collection of Admiral Thomas C. Kinkaid, USN, 1973)

From 1938 to 1941, Kinkaid was a naval attaché in Italy and Yugoslavia. In the months prior to U.S. entry into World War II, he commanded a destroyer squadron. Promoted to rear admiral in 1941, he assumed command of a U.S. Pacific Fleet cruiser division. His cruisers defended the aircraft carrier USS Lexington during the Battle of the Coral Sea and USS Hornet during the Battle of Midway.

After that battle, he took command of Task Force 16, a task force built around the carrier USS Enterprise, which he led during the long and difficult Solomon Islands campaign, participating in the Battles of the Eastern Solomons and the Santa Cruz Islands. Kinkaid was placed in charge of the North Pacific Force in January 1943 and commanded the operations that regained control of the Aleutian Islands. He was promoted to vice admiral in June 1943.

In November 1943, Kinkaid became Commander Allied Naval Forces South West Pacific Area, and Commander of the Seventh Fleet, directing U.S. and Royal Australian Navy forces supporting the New Guinea campaign. During the Battle of the Surigao Strait, he commanded the Allied ships in the last naval battle between battleships in history.

Some of the older naval aviation officers and enlisted men who fought in WW2 were undoubtedly involved in airship operations during the 1920s and 1930s.

2019 ZR1 Corvette

The Rockwell B-1 Lancer[N 1] is a supersonic variable-sweep wing, heavy bomber used by the United States Air Force. It is commonly called the "Bone" (from "B-One").[1] It is one of three strategic bombers in the U.S. Air Force fleet as of 2021, the other two being the B-2 Spirit and the B-52 Stratofortress.

The B-1 was first envisioned in the 1960s as a platform that would combine the Mach 2 speed of the B-58 Hustler with the range and payload of the B-52, and was meant to ultimately replace both bombers. After a long series of studies, Rockwell International (now part of Boeing) won the design contest for what emerged as the B-1A. This version had a top speed of Mach 2.2 at high altitude and the capability of flying for long distances at Mach 0.85 at very low altitudes. The combination of the high cost of the aircraft, the introduction of the AGM-86 cruise missile that flew the same basic profile, and early work on the stealth bomber all significantly affected the need for the B-1. This led to the program being canceled in 1977, after the B-1A prototypes had been built.

The program was restarted in 1981, largely as an interim measure due to delays in the B-2 stealth bomber program. This led to a redesign as the B-1B, which differed from the B-1A by having a lower top speed of Mach 1.25 at high altitude, but improved the low-altitude speed to Mach 0.96. The electronics were also extensively improved, and the airframe was improved to allow takeoff with the maximum possible fuel and weapons load. Deliveries of the B-1B began in 1986 and formally entered service with Strategic Air Command (SAC) as a nuclear bomber that same year. By 1988, all 100 aircraft had been delivered.

With the disestablishment of SAC and its reassignment to the Air Combat Command in 1992, the B-1B was converted for a conventional bombing role. It first served in combat during Operation Desert Fox in 1998 and again during the NATO action in Kosovo the following year. The B-1B has supported U.S. and NATO military forces in Afghanistan and Iraq. The Air Force had 62 B-1Bs in service as of 2016. The Northrop Grumman B-21 Raider is to begin replacing the B-1B after 2025; all B-1s are planned to be retired by 2036.

The B-1 was first envisioned in the 1960s as a platform that would combine the Mach 2 speed of the B-58 Hustler with the range and payload of the B-52, and was meant to ultimately replace both bombers. After a long series of studies, Rockwell International (now part of Boeing) won the design contest for what emerged as the B-1A. This version had a top speed of Mach 2.2 at high altitude and the capability of flying for long distances at Mach 0.85 at very low altitudes. The combination of the high cost of the aircraft, the introduction of the AGM-86 cruise missile that flew the same basic profile, and early work on the stealth bomber all significantly affected the need for the B-1. This led to the program being canceled in 1977, after the B-1A prototypes had been built.

The program was restarted in 1981, largely as an interim measure due to delays in the B-2 stealth bomber program. This led to a redesign as the B-1B, which differed from the B-1A by having a lower top speed of Mach 1.25 at high altitude, but improved the low-altitude speed to Mach 0.96. The electronics were also extensively improved, and the airframe was improved to allow takeoff with the maximum possible fuel and weapons load. Deliveries of the B-1B began in 1986 and formally entered service with Strategic Air Command (SAC) as a nuclear bomber that same year. By 1988, all 100 aircraft had been delivered.

With the disestablishment of SAC and its reassignment to the Air Combat Command in 1992, the B-1B was converted for a conventional bombing role. It first served in combat during Operation Desert Fox in 1998 and again during the NATO action in Kosovo the following year. The B-1B has supported U.S. and NATO military forces in Afghanistan and Iraq. The Air Force had 62 B-1Bs in service as of 2016. The Northrop Grumman B-21 Raider is to begin replacing the B-1B after 2025; all B-1s are planned to be retired by 2036.